Working Memory Deficits Following TBI

| Select a project below to learn more: |

|

| Mechanisms Underlying Working Memory |

|

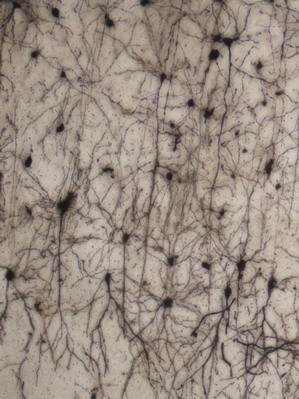

Almost two million people sustain traumatic brain injury (TBI) each year in the United States alone, with most reporting deficits in working memory that can persist for years after the initial injury. While direct damage to the prefrontal cortex can result in working memory dysfunction, impairments can also be observed in the absence of overt neuronal loss within this structure. Studies performed in humans, monkeys and rodents have shown that the neurotransmitter dopamine plays a critical role in working memory, with both excessive and insufficient dopamine receptor D1 stimulation impairing working memory performance. We have observed that TBI causes a rapid and sustained increase in prefrontal dopamine levels. This increase, via stimulation of post-synaptic D1 receptors on inhibitory neurons, increases the expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), the rate-limiting enzyme in GABA synthesis. We found that both altered dopamine- and GABA-mediated neurotransmission contribute to TBI-associated working memory dysfunction. While these neurotransmitter imbalances cause working memory dysfunction early after injury, our recent results show that working memory deficits at later time points is associated with morphological changes (e.g. reduced dendrite length and increased spine numbers) in the pyramidal neurons within the prefrontal cortex. We are currently evaluating how the changes in neurotransmitter levels seen acutely following injury contribute to these lasting morphological changes.

Almost two million people sustain traumatic brain injury (TBI) each year in the United States alone, with most reporting deficits in working memory that can persist for years after the initial injury. While direct damage to the prefrontal cortex can result in working memory dysfunction, impairments can also be observed in the absence of overt neuronal loss within this structure. Studies performed in humans, monkeys and rodents have shown that the neurotransmitter dopamine plays a critical role in working memory, with both excessive and insufficient dopamine receptor D1 stimulation impairing working memory performance. We have observed that TBI causes a rapid and sustained increase in prefrontal dopamine levels. This increase, via stimulation of post-synaptic D1 receptors on inhibitory neurons, increases the expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), the rate-limiting enzyme in GABA synthesis. We found that both altered dopamine- and GABA-mediated neurotransmission contribute to TBI-associated working memory dysfunction. While these neurotransmitter imbalances cause working memory dysfunction early after injury, our recent results show that working memory deficits at later time points is associated with morphological changes (e.g. reduced dendrite length and increased spine numbers) in the pyramidal neurons within the prefrontal cortex. We are currently evaluating how the changes in neurotransmitter levels seen acutely following injury contribute to these lasting morphological changes.